Appalachian Prison Book Project: an Interview with Katy Ryan

What inspired you to start the Appalachian Prison Book Project?

In 2004 at West Virginia University, I was teaching a graduate class on the literature and history of incarceration in the U.S. The students were struck by how many writers in prison mentioned the need for better access to education and books. We did some research and discovered there were almost no organizations sending free books to people incarcerated in the Appalachian region. We decided we would create a project and mail books to people imprisoned in West Virginia and five surrounding states.

It took a couple years to raise money, collect donated paperbacks, and find a work space. Once we sent word to people in prison that we existed, we were inundated with letters. Within a few weeks we were receiving letters from prisons and jails across the country. We’ve been responding to letters ever since, for the past twenty years—and have mailed over 65,000 books.

So APBP was really inspired by books and writers—by Jimmy Santiago Baca, Assata Shakur, Malcolm X, John Wideman, Etheridge Knight.

How has the program evolved or changed since its start?

We never imagined when we started where the letters would take us.

In our early years we were focused on responding to the hundreds of letters that arrive each week. We needed to build up a volunteer base and establish processes for selecting books, mailing packages, and tracking data. But the letters moved us to do more. We wanted to go inside with books.

In 2014, we created our first book club in a federal prison for women. We then expanded to men’s federal prisons and a Pennsylvania state prison. These reading and writing groups consist of 10 or so incarcerated readers and 2-3 volunteers. The group decides together on what books to read and meets every two weeks. The discussions are hard to describe—always both intensely focused on the book and incredibly honest. Members often bring their own writing to share. One woman drew with colored pencils a gorgeous underwater scene in response to Adrienne Rich’s poem, “Diving into the Wreck.”

I started teaching college courses in prisons around 2017, and APBP began to raise money to pay for books and supplies. A couple years later, APBP was able to pay tuition costs as well. In 2021, we launched an education scholarship awarded annually to people released from prison in West Virginia who enroll in a college or university in the state. APBP also has a pen pal program, online book discussions, and lots of community events. But responding to letters remains the heartbeat of the organization.

Were there any challenges you faced when starting the program as well as in recent years?

Our biggest challenge early on was fundraising. We are a volunteer organization that relies entirely on donations and small grants. We had a lot to learn about how to build and sustain this work. Money remains a challenge, but we also want to ensure we are investing our energy in the most impactful and needed ways. Setting priorities can be a challenge when the everyday work is so labor-intensive.

We also try to support one another. We want to be careful with one another.

How have you noticed this program impacts members supporting the cause as well as those who are receiving books and letters?

People tell us in letters how much they rely on books for information, entertainment, healing, and escape. Reading can help with legal cases, with health and relationships. People tell us how much much they enjoyed a book — or did not! We love to hear all of it.

And books make their way into many readers’ hands. Folks often pass a book onto a cellmate or to the prison library. They recommend it to a family member or friend.

In turn, the letters we receive are an education for all of us. Not many people write letters anymore, and it’s a moving experience to open letter after letter and hear directly from people who are searching for something. Who are trying to rebuild their lives with few resources. When people volunteer who do not know a lot about the system, these personal handwritten words activate them to want to understand and learn more.

We do our best to send people what they want to read. Every Saturday on social media, we ask APBP followers to donate books that have been requested and that we don’t have on the shelves. It is amazing to see how quickly and enthusiastically supporters answer the call. And this has an impact far beyond our region.

How has your work with the Prison & Justice Initiative at Georgetown overlapped with the Appalachian Prison Book Project, if at all?

Last fall, APBP donated 75 dictionaries to students in PJI education programs at the DC Jail and Patuxent Institution in Jessup, MD. I am sure there will be many more chances to partner.

In your own words, what is the Prison & Justice Initiative at Georgetown? How has this program changed and/or developed since its start?

PJI is the daily practice of creating a better world. The PJI team is filled with people who believe in education and liberation and who know that locking up people for short or extreme sentences with no opportunities to grow and develop does not create public safety or prevent harm. It obviously does not reduce recidivism. PJI believes that education, not only through classes but through public and community events, has a role to play in the larger struggle to reverse the trajectory of our criminal legal system.

How have students impacted the outcomes of this program?

Students impact everything we do. They are highly engaged and interested in program design and outcomes. They share feedback on courses and the overall curriculum. They have ideas about how to improve reentry and student support and how to create pathways to campus post-release.

Students also provide tremendous support to one another. They want to move forward together. They praise each other’s strengths. Listen carefully to one another and respond with generosity and humor. It’s an honor to be part of this kind of learning.

How does art play a role (if any) in the Prison & Justice Initiative as well as APBP.

I think a lot about the power of beauty in prison. I teach American drama in the DC Jail and at Patuxent, and students collaborate on performances in response to the plays we are reading. They make props out of available materials. Roses from toilet paper, seagulls from tissue paper. And when the students step up to do their performance, the energy in the room changes. We all feel it. And the creativity is off the charts. Students have written original music and poetry. They have delivered devastating and hilarious scenes. They surprise themselves with beauty.

One student in my class is a painter, and he told me that as he watched students perform, in response to Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf, he could see the image for his next painting. Art is generative and life-giving like this, especially in places designed to isolate and silence.

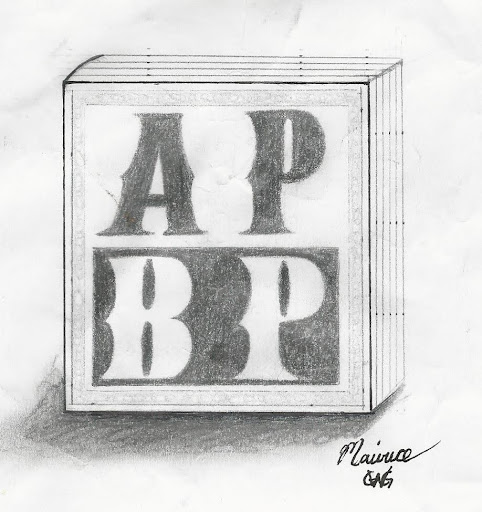

Art is also essential at APBP. People draw pictures of butterflies and cartoon characters and waterfalls on envelopes or include paintings and drawings with their letters. We have a couple large albums filled with art. Maurice Gayles, a member of one of our first book clubs, created the APBP logo when he was still incarcerated. It means the world to us.