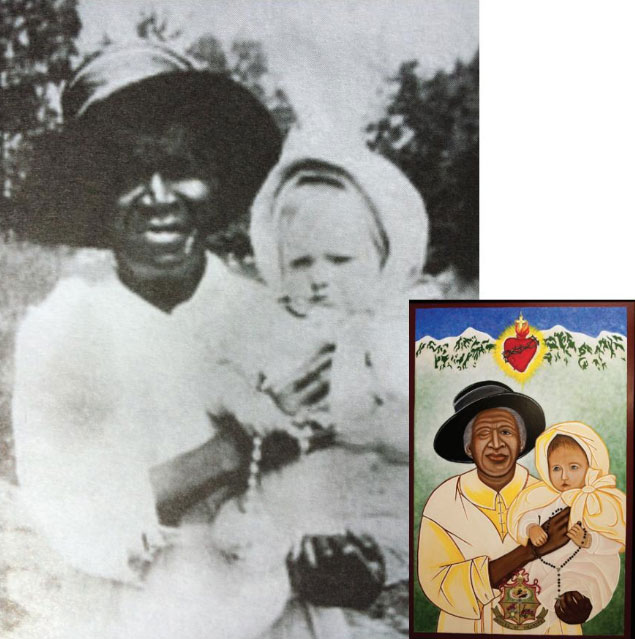

From Slave to Saint

Regis leader guides effort to canonize Denver woman

On Lowell Boulevard in northwest Denver, a beautiful Victorian home sits just across the street from the Regis campus. Inside that house, more than a century ago, a tiny and frail former slave swept the floors, made the beds and tidied the rooms. Blinded in one eye by a slave owner’s whip and hobbled by arthritis, she then would have walked to a boardinghouse downtown where she lived, and might have crossed the campus of what then was known as Sacred Heart College to shorten the journey.

That woman, Julia Greeley, born a slave in Missouri between 1833 and 1848, is now a candidate for Catholic sainthood.

As an emancipated adult, Greeley worked for the sister of Julia Pratte Gilpin, who later became wife of Colorado’s first territorial governor. It was that association that brought Julia Greeley to Colorado in 1878, where she would earn a meager living cooking and cleaning homes. She became a devout Catholic who worshipped with the Jesuits, and began the life of charitable acts that would make her beloved during her lifetime and a candidate for Catholic sainthood.

Although she had very little herself – and occasionally even needed help from local charities – Greeley devoted much of her life to helping those in need. She tirelessly walked across Denver, often pulling a wagon behind her, collecting whatever she could for needy families.

In his biography of Greeley, In Service of the Sacred Heart: The Life and Virtues of Julia Greeley, Rev. Blaine Burkey, O.F.M. Cap., writes, “On one occasion, a priest of the Sacred Heart parish found her pushing a baby carriage along at night. She had found a poor family that needed it. So, she had gone out and begged for it. On another occasion, one of the Jesuits met her carrying a broken doll…she told him that she was taking it home to fix up…to give it to some child.”

When she died in 1918, her ceaseless efforts to aid the poor had made Greeley so well-known in Denver that an estimated 1,000 mourners came to Loyola Chapel where her body lay to pay their respects.

“She was a woman with a wide-winged spirit,” wrote Frances Wayne, a Denver Post reporter who covered Greeley’s funeral. As recounted on the website of Denver’s Julia Greeley Home, which assists women facing homelessness, Wayne wrote that her legacy included “eighty-five years of worthy living…unselfish devotion…and a habit of giving and sharing herself and her goods.”

In 2016 the Vatican granted permission to open a cause for Greeley’s sainthood, naming her a Servant of God, the title granted to those under consideration for canonization. In December of that year, Rev. Samuel J. Aquila, archbishop of the Catholic Diocese of Denver, officially opened Greeley’s case for canonization.

The Denver Archdiocese assembled a committee to begin the research that would ultimately comprise the case for Greeley’s sainthood. David Uebbing, chancellor of the Archdiocese, was chosen to serve as vice postulator for the committee. The postulator is responsible for promoting the proposed saint’s cause locally, and the person responsible for communicating with the Vatican as the cause moves ahead.

“I was definitely honored to be asked to serve as the vice postulator. I never imagined I would do that in my entire life. It's my favorite thing I've done as chancellor. It's just so edifying to be close to the process of looking at a person's life and seeing how they've impacted so many people,” Uebbing said.

Barbara Wilcots, Ph.D., vice president of student affairs at Regis, who also was part of the committee, described it as a fascinating experience and said Greeley demonstrated values as a Catholic that are relatable to the average person.

“Many of the saints seem like superheroes but Julia felt real and accessible. As a Black Catholic woman, I felt a true connection to a rich history that for too long was rendered invisible,” Wilcots said.

Currently there are no Black saints from the United States. Although there are an estimated three million Black Catholics in the U.S., they comprise just four percent of the church population, and represent only six percent of the nation's Black adults. Still, many faithful believe recognition is long overdue for those Black people who led selfless lives of faith in this country.

Greeley is one of six Black Catholics from the United States being considered for sainthood. In December 2021, a group of activists from St. Ann’s Catholic Church in Baltimore sent 1,500 letters asking Pope Francis to “immediately” canonize those six. In addition to Greeley, those candidates are Henriette DeLille, who founded the Sisters of the Holy Family; Mary Elizabeth Lange, who founded the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the country’s first religious congregation of women of African descent; Pierre Toussaint, a former slave who helped raise money for St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York but was not permitted to attend the cathedral’s opening because of his race; John Augustine Tolton, the first openly Black ordained priest; and Thea Bowman, a 20th century Franciscan sister, educator and evangelist.

University of Notre Dame history Prof. Kathleen Sprows Cummings told CNN that the canonization process generally takes decades, and that one roadblock to naming Black saints can be the cost of the process, which often involves gathering voluminous documents, and, as in the case of Julia Greeley, travel.

Building the case for Greeley was a challenge. As was the case with many enslaved people, she never learned to read or write, so the committee did not have any of her writings to rely on.

Uebbing and another member of the Greeley canonization committee, Kevin Knight, traveled to Hannibal, Mo., where Greeley had lived and had been enslaved. Knight said they worked to document Greeley’s existence and turn over every stone to look for information about her early life.

While the process was long, Knight said he felt honored to be a part of it and admires her commitment to her faith. “I would say just how just how powerful Eucharistic devotion really is there's just no way to explain it. There was something about her works of mercy that truly were works of mercy because she was so centered,” Knight said.

The committee did have the aid of a small group of faithful men and women working on Greeley’s behalf. Since 2011 the volunteers of The Julia Greeley Guild have been dedicated “to extending Julia’s fame for sanctity, proposing her as a model of Christian virtue, encouraging private devotion to her, and helping cover some of the expenses of her Cause for Canonization,” according to their website. In addition, the group also raises money to help with the expenses of pursuing her cause.

Mary Leisring, president and executive director of the guild, believes Greeley was chosen by God to do charitable work despite the challenges she faced, and believes Greeley’s entire life is a model.

“She stands out as a person, that I would like to imitate…I try to think of Julia and what would Julia do in a case like this? She walked the streets of Denver…and she never wavered as to who to give things to or who to share things with,” Leisring said.

The committee also had church records to help them. On June 26, 1880, Greeley was conditionally baptized at Denver’s Sacred Heart Catholic Church by Rev. Charles M. Ferrari, S.J., who recorded the event in a handwritten sacramental record that can still be viewed at the church. Since they did not know whether Greeley had been baptized before, they performed what is known as a conditional baptism.

Rev. Eric David Zegeer, current pastor at Sacred Heart, in what is now known as Denver’s Five Points neighborhood, said no one really knows how Greeley first came to that church. “For reasons I'm not aware of…she saw this church and came in to pray...and I think it's not implausible to suspect that had she entered other Catholic churches in Denver or other Christian churches, she may not have been welcomed, simply because she was a free Black [former] slave woman. But the Jesuits at that time, I think heroically, welcomed her.”

Not all members of the church welcomed her, but according to various reports, the church pastors vigorously defended her right to worship alongside white parishioners.

Greeley reportedly went to church daily, and from there drew inspiration for what became her life of selfless charity. In 2012, the Julia Greeley Guild published In Service of the Sacred Heart: The Life and Virtues of Julia Greeley by Rev. Blaine Burkey, O.F.M. Cap. The book includes testimonials, newspaper articles and other information about Greeley.

"Her charity was so great that only God knows it's extent. She was constantly visiting the poor and giving them assistance from her own slender means."

-Rev. Blaine Burkey, O.F.M. Cap.

In Burkey’s book, he notes, “Her charity was so great that only God knows its extent. She was constantly visiting the poor and giving them assistance from her own slender means. When she found their needs so great that she could not help them with her own goods, she begged for them. Her charity was as delicate as it was great.

“She realized that white people, no matter how poor, might feel a little sensitive in receiving assistance from an old colored woman, so she went at night to their homes to deliver the goods she had begged, in order to keep the neighbors from seeing her.” Yet, according to Burkey, Greeley was so poor herself that “the city charity department had been furnishing her with fuel and groceries.”

Greeley had a special concern for firefighters, whom she felt were risking their lives almost daily to protect Denver residents, at a time when wooden homes and other buildings caught fire regularly. She was known to walk to fire stations across town praying for firefighters and handing out prayer leaflets. It was estimated she walked 20 miles each month to firehouses despite suffering from severe arthritis.

Greeley had a particular devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, one of the most widely practiced of Catholic devotions, and died on June 7, 1918, the feast day for the Sacred Heart. In 2017, her body was exhumed from its grave at Mt. Olivet Catholic Cemetery in Wheat Ridge, Colo., by a team led by Christine Pink, Ph.D., of Denver’s Metropolitan State University. According to the Julia Greeley Guild website, the exhumation revealed that Greeley had an extra rib. Pink determined Julia’s height to have been five feet, one inch, and said that her spine, legs, and hands were covered with arthritis.

Greeley’s remains now lie in a marble coffin at the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception in downtown Denver, and the Vatican now has 36 volumes of documents, totaling 11,750 pages, detailing Greeley’s life and deeds, to review as they determine whether she is deserving of sainthood.

Those who are devoted to Greeley’s cause wait, and continue to work on her behalf. Whatever the Vatican decides, Leisring said Greeley’s life and works inspire her. Her goal, Leisring said, “is to try to make a difference in this world, even though you have all of these obstacles. Trying to eradicate racism and trying to help people understand that racism is a sin. And that we're all created by God.”